The thing about bi-polar

Some of my first childhood memories are of my mother sitting at our dining table in the kitchen of our riverside home in Ulmarra, NSW, telling whoever dropped in for a “cuppa” that my Dad was crazy. Before I was born in 1971, my Dad, then 23 years old, accidentally set fire to himself, causing severe burns to his entire body after the backyard incinerator blew up on him. The burns he received to his body left him in the hospital for several months, and he took opioid medications as a result for the rest of his life for the “pain”.

On a random day in August 1984, when I was 7, Mum packed my sisters and me up in the back of her Nissan Skyline and left my father, moving us across the country to Adelaide. This separation was abrupt, not just for Dad, but for us girls, and it certainly changed the trajectory of all our lives. The months and years that followed were filled with chaotic episodes, some of which included Dad abducting my eldest sister and me from school, fleeing with us across the country, and driving drunk as he drank a bottle of white rum and consumed endless amounts of prescribed opioids and antipsychotics. It was after this particular incident that Dad was hospitalised for a substantial amount of time in a mental institution, as it was known in the 80s, and it was after that we were told as children that Dad was Schizophrenic and a severe alcoholic. No more information or education was given to us children back then, and we were often left in his care without any idea of how to navigate the severe episodes he would have, some resulting in him being aggressive and physically abusive towards us. I lived with Dad for a brief six months when I was 15, after my Stepdad had kicked me out, and it was here that I saw the full force of his alcoholism and prescription pill abuse. I saw the Doctors he regularly visited give my Dad endless medication for his problems and conditions. Still, he never had any therapy and more notably, in my memory bank, Dad would sell his medications for sex with prostitutes while I was left to babysit their little toddlers in our lounge room.

In my early 20s, Dad was living in the back shed of my childhood friend’s home, working a minimum wage job and still struggling with his mental illness and alcoholism. At this point, he came to live with my then-husband and me in Townsville, where I helped him by managing his financial affairs with hopes of stabilising his mental health. I was able to help with the former but not the latter. Back in the late 90s, I was too struggling with my mental health, and without the knowledge of childhood trauma and toxic relationship cycles, Dad and I just fed into a situation that had him move out of my home and into a small flat with a workmate. I then moved away from Townsville, and Dad stayed there, working in the mining sector. Almost a decade later, Dad followed me and my sisters to Adelaide, where I re-settled him into a small rental unit and began managing his financial matters again. This time, I was more proactive with his mental health issues, taking him to psychiatrists, along with getting his teeth fixed and other addict health issues sorted. Dad didn’t engage in any therapy, but the psychiatrist he saw at this juncture diagnosed Dad with BiPolar disorder, so this led to more prescriptions for his “conditions”. After looking after Dad and his life for another few years, I again began to suffer a deep depression, which resulted in my first trip to a private hospital for alcoholism and severe depression and anxiety in 2011.

When I went to rehab for the first time in 2011, I gave the treating medical team my family history. While my Dad was diagnosed, Schizophrenic and/or Bipolar, it was discussed at length by my treating psychiatrist that this diagnosis didn’t fit me, but being severely anxious and depressed did, and he told me that was because of my alcoholism. I was prescribed a drug called Seroquel at this point, which was a drug used for Bi-Polar, but I was told by my treating psychiatrist it was a sleep aid to assist my crippling insomnia. I was a depressed person who couldn’t sleep, and now, looking back on it, I was working 18-hour days sometimes. My brain seemed never to be turned off unless I drank it to sleep or took a Seroquel or 3. In 2012, I returned to the same private hospital again for alcoholism, but it had gotten worse. It was at this time I was tried on a few other prescriptions of varying kinds, only to return to Seroquel. But we worked on childhood trauma here, and I began at this point to absorb what they were teaching me in the therapy I was having; well, that was until it was too painful to feel the emotions I had long suppressed, and I had to numb it out by taking Seroquel and drinking Vodka.

It wasn’t until 2018 that I learned for myself that my conditions were trauma-related and that Seorquel was not helping me in the long term when my health began to worsen as hormonal issues started to rage in my body; I was a year sober, so alcohol was no longer contributing to my worsening health, so to me, it had to be the prescription antipsychotics and antidepressants they had me on to treat my new diagnosis of C-PTSD. I was proven right in 2022 when I was diagnosed with a prolactinoma. Now, I only use Medicinal Cannabis as a treatment for just about everything “wrong” with my physical and mental health; this has taken time, but I am on the path of recovery that should see me living out my life to 100+ years. Unfortunately, my Dad’s life didn’t have a happy ending; in fact, he had an unfortunate and lonely ending, one that is going to haunt me for the rest of my days. Dad died in November 2023, an alcoholic and taking endless amounts of prescribed medications at the age of just 74. His body gave out under the pressure of years of abuse. I know that the drugs they had him on all his life didn't bring him any well-being or quality; they only took away, they robbed him of being a father to me, and they robbed him of being himself; he was never able to grow into the man who he should have been.

If nothing else, I hope that advocating on these matters by sharing my story can change just one life and help the medical industry reassess the way mental illness is categorised and diagnosed. I share the Holistic Psychologist Dr Nicole LePera's views on BiPolar and other personality disorders, and that is, they are primarily a trauma response to grief, and the grief most likely stems from adverse childhood experiences.

Are you a little overwhelmed by all this diagnosis of psychological disorders talk?

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) refer to potentially traumatic events that occur during childhood, including abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction, such as parental substance abuse or mental health issues. Research indicates that these experiences can have lasting impacts on an individual's psychological and physical health, increasing the risk for conditions such as depression, anxiety, and chronic illnesses later in life. The ACEs framework highlights the importance of recognising and addressing these experiences in clinical and community settings to provide support and intervention, ultimately fostering resilience and healthier outcomes for those affected. Acknowledging the prevalence and impact of ACEs is essential for developing effective prevention strategies and enhancing overall well-being.

Alcoholism also referred to as alcohol use disorder, is a long-term condition defined by a person's inability to regulate their drinking despite adverse consequences. It frequently includes a compulsion to drink, culminating in physical dependence and withdrawal symptoms when alcohol is not consumed. Individuals with alcoholism often place alcohol above their responsibilities, relationships, and personal health. This condition can stem from genetic, psychological, and social influences, significantly affecting a person's emotional, mental, and physical health. Treatment generally involves a mix of therapy, support groups, and, in some instances, medication to assist individuals in regaining control over their lives and diminishing their reliance on alcohol.

Personality disorders are a group of mental health conditions marked by enduring patterns of behaviour, cognition, and inner experience that significantly deviate from cultural expectations. These patterns often manifest in pervasive and inflexible ways and can lead to distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other crucial areas of functioning. Individuals with personality disorders may struggle with relationships, self-identity, and emotional regulation. The disorders are generally classified into three clusters: Cluster A (odd or eccentric behaviours), Cluster B (dramatic, emotional, or erratic behaviours), and Cluster C (anxious or fearful behaviours), each encompassing various specific diagnoses. Treatment options typically include therapy and, in some cases, medication to help manage symptoms.

Schizophrenia has a complex history that dates back thousands of years, with early descriptions of symptoms found in ancient texts from civilisations such as Egypt, India, and Greece. The term itself was introduced in 1908 by Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, who sought to encompass a range of disorders exhibiting a split between thought processes and reality. Before this, the condition was often misunderstood and misdiagnosed as a form of insanity or demonic possession. Throughout the 20th century, the understanding of schizophrenia evolved considerably, influenced by advances in psychology, neuroscience, and pharmacology. By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, a more nuanced understanding emerged, recognising the interplay of genetic, environmental, and social factors in the disorder's manifestation. Today, schizophrenia is viewed as a multifaceted mental health condition requiring comprehensive treatment approaches.

Bipolar disorder, once known as manic-depressive illness, has a rich history that spans thousands of years and crosses many cultures. Some of the earliest accounts of this condition can be found in ancient civilisations, where the Greeks and Romans documented symptoms that resemble what we now recognise as bipolar disorder. Notably, the physician Hippocrates was among those who carefully noted these experiences. Fast forward to the 19th century, when the insightful French psychiatrist Jean-Pierre Falret coined the term "la folie circulaire" to capture the cyclical nature of the disorder, which genuinely emphasises the dramatic mood swings that people face. Thanks to significant advancements in psychiatry and psychology by the mid-20th century, we gained a deeper understanding of bipolar disorder, leading to its status as an official mental health diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Over the years, the classification of bipolar disorder has evolved, with the DSM-5 now recognising various types, which underscores the complexity and diversity of mood dysregulation that defines this multifaceted condition.

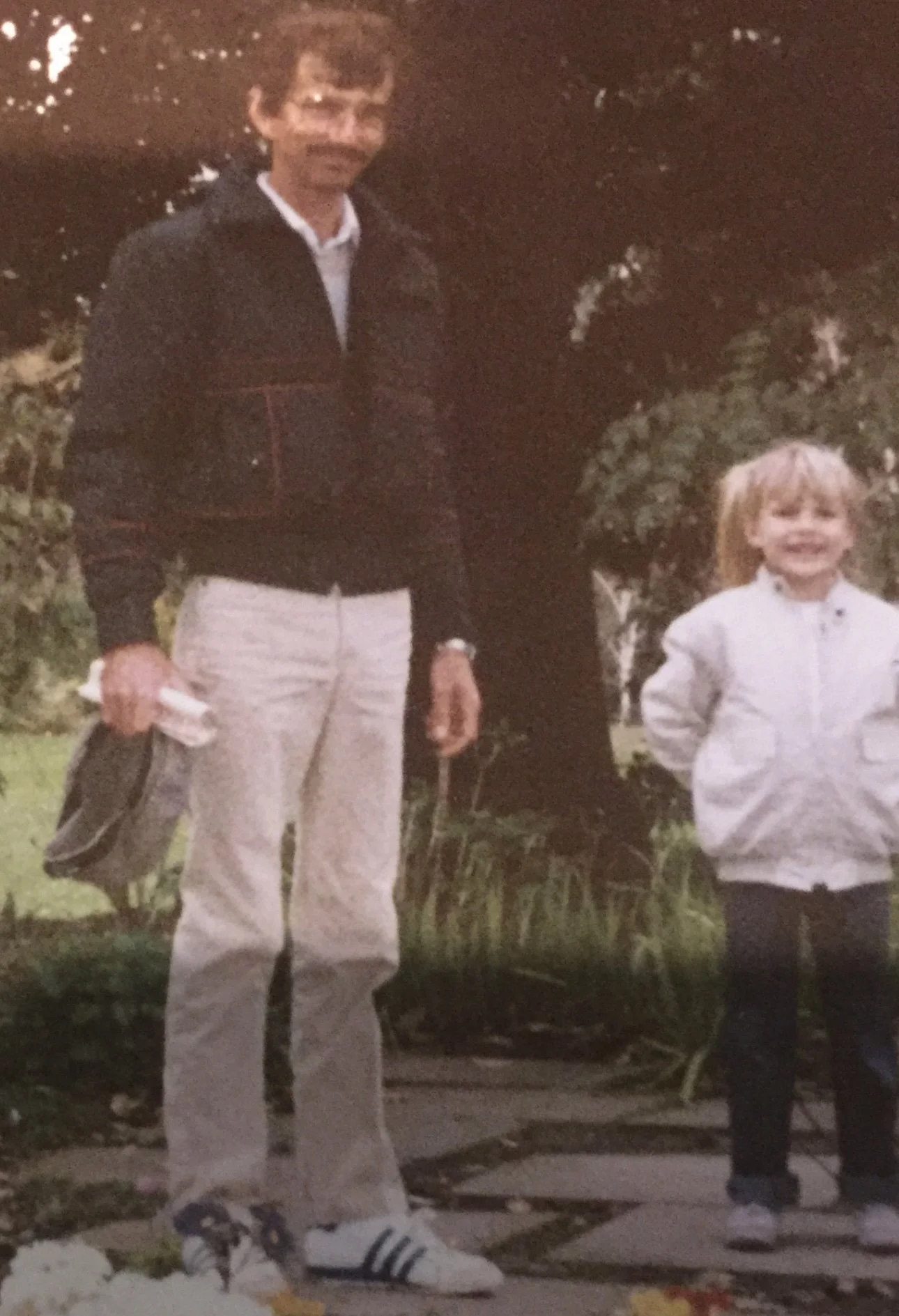

This post is dedicated to my late father, Jeffrey Ross Eggins.

“Daddy, May the peace you sought on this earth, you’ve found in the afterlife - I will love you forever”

Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD) emerged as a distinct diagnosis in the field of psychology following observations of individuals who experienced prolonged exposure to traumatic events, particularly in cases of sustained interpersonal abuse, such as childhood neglect or domestic violence. The concept gained traction in the 1990s when the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), included a discussion of the effects of chronic trauma, setting it apart from traditional Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The recognition of C-PTSD was further supported by research indicating that its symptoms encompass emotional dysregulation, relationship difficulties, and negative self-perception, extending beyond the typical PTSD symptoms of re-experiencing and hyperarousal. The World Health Organization subsequently acknowledged C-PTSD in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11), consolidating its importance in understanding the complexities of trauma and its long-lasting impacts on mental health.

Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) has a complex history that dates back to the early 20th century. Initially described by psychoanalyst Adolph Stern in 1938, BPD was referred to as a "borderline state," indicating patients who exhibited symptoms that fell between psychosis and neurosis. Over the following decades, the understanding of BPD evolved, leading to increased recognition and research, particularly in the 1980s, when the disorder was officially included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980. This inclusion marked a significant step in acknowledging the condition and its impact on individuals. Since then, ongoing research has refined the understanding of BPD, emphasising the importance of biological and environmental factors in its development and promoting practical therapeutic approaches.

Psychosis is a serious mental illness in which an individual loses touch with reality, leading to hallucinations and delusions. On the other hand, neurosis is a less severe mental condition marked by anxiety, worry, and distress but without a complete separation from reality. The primary distinction between psychosis and neurosis lies in their severity. In essence, psychosis is recognised as a more serious affliction that can significantly disrupt daily life, while individuals with neurosis usually can manage their daily activities with appropriate treatment.

Key points about psychosis:

- Symptoms: Hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren't present), delusions (firmly held false beliefs), and disorganised thinking.

- Reality Impact: Major loss of contact with reality.

- Severity: Viewed as a more severe mental disorder.

- Examples of disorders: Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder featuring psychosis.

Key points about neurosis:

- Symptoms: High levels of worry, anxiety, compulsive thoughts, and depression.

- Reality Impact: Retains connection to reality.

- Severity: Classified as a milder mental condition.

- Examples of disorders: Anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Important to note that although "neurosis" is less frequently used in contemporary psychiatric diagnostics, it remains conceptually useful for describing anxiety-related symptoms that do not involve a break from reality.